For my PhD, I worked with my amazing advisor

Prof. Carolyn (Lindy) McBride at Princeton University,

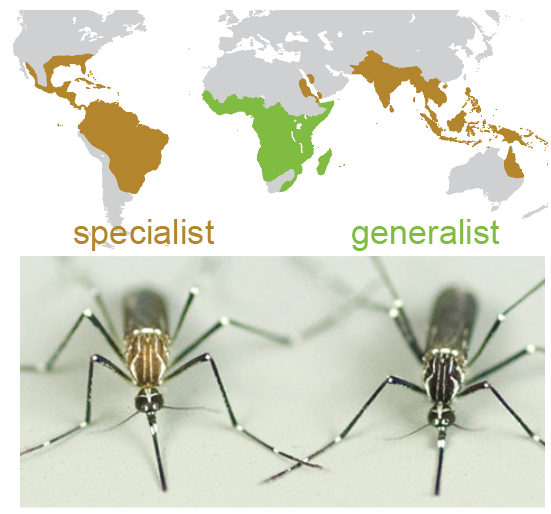

on the evolution of olfactory circuits in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aeygpti.

We want to understand at the neural level why these mosquitoes became preferentially attracted to human odor during evolution, which makes them devastatingly efficient for spreading diseases to humans.

(Links to related publications are underlined)

Study system: evolution of olfactory circuits in mosquitoes

My PhD research focused on the evolution of olfactory circuits in the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. We believe it’s a fantastic system to understand the principles of how neural circuits evolve, along with important practical applications.

Our research also has important practical applications, just imagine if we can make these dangerous mosquitoes dislike human odor once we understand how it works!

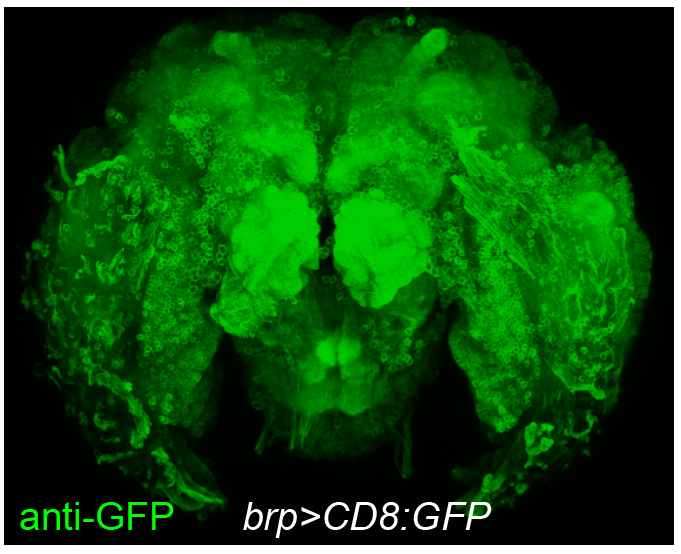

Development of neurogenetic tools in mosquitoes

Although non-model organisms have all these cool behaviors, one challenge of working with them is the limited number of tools that are available, especially neurogenetic reagents that provide access to neural circuits. In Drosophila or other model organisms, the conventional method of generating transgenic lines is fusing the promoter of target gene to a report or effector, then inserting into random location of the genome with transposons. Unfortunately in mosquitoes, this method performs poorly, which underlies the scarcity of neurogenetic reagents. To study biologically interesting questions, we first needed to create those reagents ourselves. Therefore, a substantial portion of my PhD work was devoted to the development of neurogenetic tools in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The ultimate goal is to make Aedes aegypti a neurogenetically tractable organism.

Neural basis of host preference in specialist mosquitoes

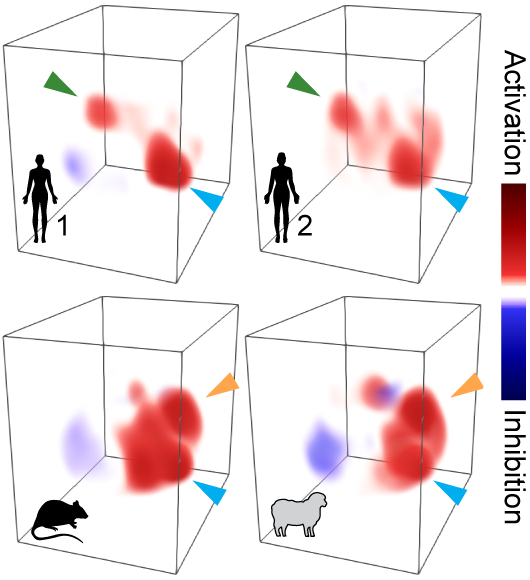

Why do specialist mosquitoes prefer human odor, over the odor of non-human animals? What’s unique about human odor and how can mosquitoes tell the difference? These questions are particularly interesting because there are hundreds of compounds in host odor and almost all components are shared between humans and animals. Probably the best way to find out is to open the heads of mosquitoes and read their “minds”. That’s exactly what we did in this research project. We developed a suite of novel genetic reagents and methods to record neural activity in the olfactory center of mosquito brain, while stimulating it with the natural, complex odor extracts of many humans and animals (figure right).

Why do specialist mosquitoes prefer human odor, over the odor of non-human animals? What’s unique about human odor and how can mosquitoes tell the difference? These questions are particularly interesting because there are hundreds of compounds in host odor and almost all components are shared between humans and animals. Probably the best way to find out is to open the heads of mosquitoes and read their “minds”. That’s exactly what we did in this research project. We developed a suite of novel genetic reagents and methods to record neural activity in the olfactory center of mosquito brain, while stimulating it with the natural, complex odor extracts of many humans and animals (figure right).

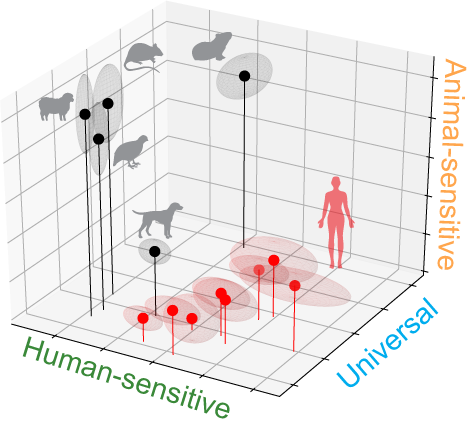

Surprisingly, we found that despite the complexity of host odor, discrimination at the neural level  could be achieved with a simple mechanism. The olfactory brain center of insects is organized into discrete units called glomeruli. We found a sparse neural representation for the host odor: only 2 to 3 glomeruli respond strongly (figure above). One glomerulus is universally activated by both human and animal odor, while the other two are human-sensitive or animal-sensitive. The relative activation of these three glomeruli nicely distinguishes human odor from animal odor, which is robust to different doses, animal species and individual human variations (figure right).

could be achieved with a simple mechanism. The olfactory brain center of insects is organized into discrete units called glomeruli. We found a sparse neural representation for the host odor: only 2 to 3 glomeruli respond strongly (figure above). One glomerulus is universally activated by both human and animal odor, while the other two are human-sensitive or animal-sensitive. The relative activation of these three glomeruli nicely distinguishes human odor from animal odor, which is robust to different doses, animal species and individual human variations (figure right).

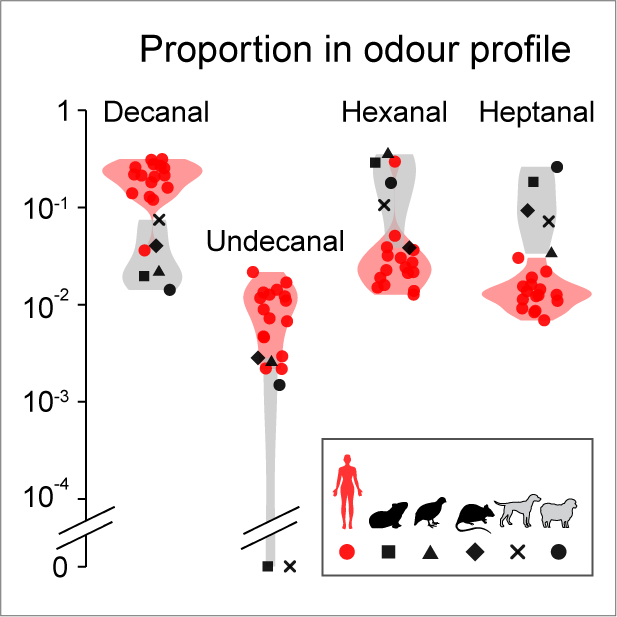

Why does human odor evoke a unique pattern of neural activity? We found that the uniqueness is primarily driven by long-chain aldehydes. Both human and animal odor have aldehydes as the major  components. However, they differ in specific kinds: human-odor is enriched for long-chain aldehydes like decanal and undecanal, but animal-odor is abundant for short-chain ones like hexanal and heptanal (figure right). Importantly, the human-sensitive glomerulus is narrowly tuned to long-chain aldehydes, which explain why it’s selectly activated by human odor. Even more interestingly, decanal is the oxidation product of sapienic acid, which is found only in human skin and may play protection roles. Taken together, it appears that during evolution, mosquiotes took advantage of the unique feature of human odor and developed a simple but robust neural mechanism to discriminate from animals.

components. However, they differ in specific kinds: human-odor is enriched for long-chain aldehydes like decanal and undecanal, but animal-odor is abundant for short-chain ones like hexanal and heptanal (figure right). Importantly, the human-sensitive glomerulus is narrowly tuned to long-chain aldehydes, which explain why it’s selectly activated by human odor. Even more interestingly, decanal is the oxidation product of sapienic acid, which is found only in human skin and may play protection roles. Taken together, it appears that during evolution, mosquiotes took advantage of the unique feature of human odor and developed a simple but robust neural mechanism to discriminate from animals.